Next month is June, aka LGBT Pride Month. In anticipation of this, and because it is good and necessary to discuss representation in pop culture and media, we present to you this look at how LGBT content has been portrayed in mainstream American comic books. This is by no means a complete history. We don’t have the space for that. But we hope you’ll appreciate this look at some of the major forces that have shaped stories and characters in the mainstream comic book medium.

THE GOLDEN AGE

The first comic books were simply reprints of comic strips featured in U.S. newspapers. One very popular strip series was Terry and the Pirates, which ran from 1934 to 1946. Hero Terry Lee had several female enemies during the series, one of whom was the Frenchwoman Sanjak, a spy for the Axis Powers who was noted for always dressing as if she were a man. When Sanjak captured Terry’s love interest April Kane it was implied that she was attracted to the young girl. Many consider this character to be the first lesbian in comics.

The Golden Age of comic books is considered to cover the 1930s until roughly 1951. During this time, sex in mainstream comics was largely limited to being implied via dialogue. Occasionally Golden Age comics featured effeminate men to serve as the butt of jokes, such as Jasper Dewgood from the Kid Eternity stories. Wonder Woman raised a few eyebrows since her backstory involved being raised on an island inhabited only by women, some of whom playfully engaged in bondage, either as part of a game or an exercise in personal power. “Tijuana bibles” also depicted popular characters in sexual situations, sometimes including same-sex contact, without having the licenses or permission to do so. No one knows for sure why they were called Tijuana bibles.

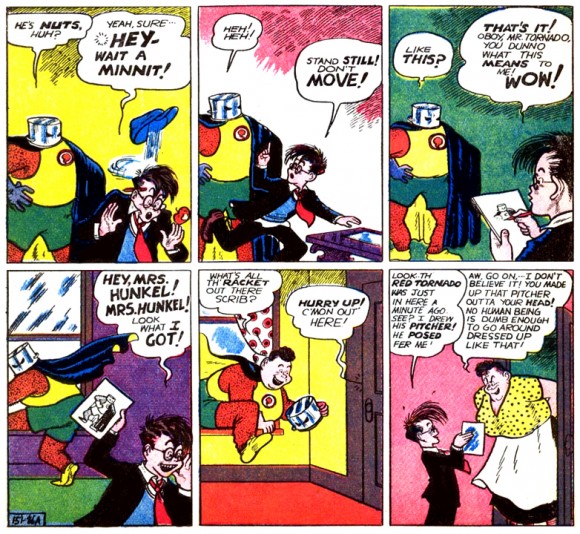

Whenever sexual themes in Golden Age comics are discussed, two cross-dressing heroes often come up. In 1940, Crack Comics #1 introduced Richard Stanton, who disguised himself as an old woman named Madame Fatal to fight crime. In 1939, the character Mrs. Maxine “Ma” Hunkel was introduced in All-American Comics #3, a supporting cast member of the comedy series Scribbly. In All-American Comics #20, a few months after Madam Fatal debuted, Ma Hunkel became the original Red Tornado, letting others think she was a male superhero. Some argue that Ma Hunkel was the first official female superhero (I’m inclined to agree, but that’s a debate for another time). Later her kids became her sidekicks, the Tornado Twins. On the villain side of things, Wonder Woman fought a criminal called the Blue Snowman who turned out to be a woman in disguise.

Superman’s stories featured a character who changed genders. The Ultra-Humanite was the first mad scientist to fight the Man of Steel, debuting in 1939. In 1940 he transferred his brain into the body of movie star Dolores Winters (later renamed Delores Winters). The Ultra-Humanite used her new form to hide from the law and seduce others into doing her bidding. She apparently died in 1940 but reappeared in comics decades later. In 1981 the Ultra-Humanite’s brain was transferred into yet a third body, an albino ape with an enlarged head. You read that right. It’s comics.

Another gender-bending story worth notice was published by Charlton Comics in Space Adventures #3 (1953). The story “Transformation” features Dr. Lars Kranston on a test flight to Mars with his girlfriend and assistant Betty. The ship crashes and the two are separated, each believing they are now alone. Lars fears he’ll go insane without activity or human contact. Going through the ship’s wreckage, he finds notes on an experimental gender reassignment process and pursues it, not just to occupy his time but also because he believes that men are inferior beings. Meanwhile, Betty learns how to survive on her own in the Martian environment. Eventually she reunites with Kranston and is heartbroken to learn that her lover is now a woman.

GayLeague.com suggests that “Transformation” was inspired by news reports a year before of Christine Jorgensen, who was born as George William Jorgensen Jr. and underwent sexual reassignment under the care of Dr. Christian Hamburger in Denmark. Jorgensen used her fame to become an advocate of transgender people. In any event, if Charlton Comics had tried to publish that story a year later, it would have never seen print thanks to Dr. Frederic Wertham and a new thing that many simply called “the Code.”

THE CODE

Starting in 1948, psychiatrist Frederic Wertham wrote and spoke publicly on his beliefs that comics corrupt children with their secret messages advocating social evils such as crime, loose sexual morals, and antisocial behavior (meaning behavior damaging to society, not to be confused with “unsocial”). This, along with bad parenting, was leading to the downfall of American society. In 1954Wertham published his arguments and conclusions in the now infamous book Seduction of the Innocent. Adolf Hitler, according to Wertham, was “a beginner compared to the comic book industry.” Superman and other heroes were clearly advocates of fascism and even anarchy, celebrating a view that their power meant they were right. Wertham pointed to Batman and Robin as a homosexual lifestyle ideal. Wonder Woman was one of the most corruptive comics, in his opinion. The Amazon’s status as an unmarried woman who was stronger than her love interest meant she was a dangerous lesbian who didn’t understand gender roles.

In truth, Wonder Woman’s creator William Moulton Marston did intend to challenge gender roles, peppering his stories with bondage images and talk about the empowerment and sisterhood. But Marston died in 1947 and the Wonder Woman comics subsequently became more tame and in line with “traditional” gender values, with the character often focusing on finding a man. Four years before Seduction of the Innocent was released, Wonder Woman left her job at the US military to become the editor of a romance advice column. Wertham was complaining about stuff that hadn’t been in her book for years.

Wertham’s evidence often involved comic panels taken out of context and misrepresented, such as when he claimed that muscle lines on a character were intentionally hidden images of female anatomy. He also often used panels and scenes taken from horror and crime comics lumped together with criticisms about superhero stories, ignoring that different books were intended for different audiences. It was confirmed in recent years that Wertham faked some of his research and didn’t hold himself to generally accepted scientific or medical standards of research, relying instead on small sample sizes and anecdotal accounts. Unfortunately this wasn’t known at the time, and enough concerned parents believed Wertham that some people held public comic book burnings.

Following the publication of Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham spoke before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency and testified that comic books were a major cause of juvenile crimes. The subcommittee report stated that the comic industry needed to gets its act in line and tone down its level of questionable morals. In response to this possible threat of further government action or regulation, the Comics Magazine Association of America formed as the new industry trade group and created the Comics Code Authority. This set of rules, often referred to simply as the Code, didn’t have any official power over publishers, but stores wouldn’t risk carrying comics that didn’t carry the Code’s literal seal of approval.

The Code had a lot of rules. You couldn’t show sex, nudity, explicitly sexual scenes, or graphic violence. There could be no exaggeration of female body parts, nor could clothing be too revealing of the female form. Artists were regularly told to remove cleavage lines (or “intermammary sulcus,” to use the medical term), even if the character was wearing a low-cut top or swimsuit. You couldn’t show how crimes were committed unless impossible technology or powers were involved. Villains couldn’t show how to conceal weapons. Heroes couldn’t be in doubt of morality or tempted by evils. Criminals could not be sympathetic. Authorities could not be shown as incompetent or corrupt unless they were directly identified as a spy or criminal only pretending to be an authority figure. References to characters suffering “physical afflictions” were to be avoided. The Code even prohibited comics from using the word “FLICK,” because there was a fear that the ink could run and merge the L and I, making them look like a letter U.

There were several guidelines concerning how sex and love were to be portrayed in stories. Three of these rules were:

- “Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at or portrayed. Violent love scenes, as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.”

- “The treatment of love-romance stories shall emphasize the value of home and the sanctity of marriage.”

- “Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.”

Combined, these three rules could prohibit any LGBT content. What constituted “sexual abnormalities” and “sex perversion” was up to the judgement of the Comics Code Authority Administrator. You could try arguing, but the CCA was a stubborn and strange lot. For instance, they sometimes sent publishers notes asking to tone down the smoke of a firing gun, because too much smoke increased the level of violence.

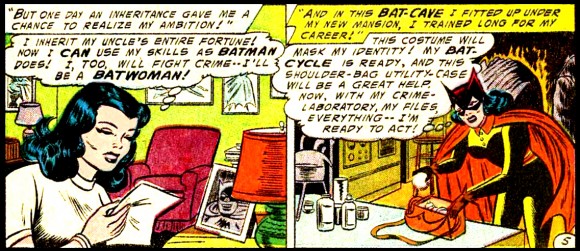

In response to Wertham’s accusations of homosexuality and the Code’s rules against sexual deviancy, DC Comics started producing stories and characters to give Batman a wholesome, family atmosphere. In 1955 readers met Ace, a German Shepard who sometimes joined the Dark Knight on missions as “Bat-Hound.” The very next year Detective Comics #233 introduced Kathy Kane aka Batwoman, an adventurer and romantic interest designed to quell any gay rumors. Her niece Betty Kane then became Bat-Girl in order to win Robin’s heart.

In response to Wertham’s accusations of homosexuality and the Code’s rules against sexual deviancy, DC Comics started producing stories and characters to give Batman a wholesome, family atmosphere. In 1955 readers met Ace, a German Shepard who sometimes joined the Dark Knight on missions as “Bat-Hound.” The very next year Detective Comics #233 introduced Kathy Kane aka Batwoman, an adventurer and romantic interest designed to quell any gay rumors. Her niece Betty Kane then became Bat-Girl in order to win Robin’s heart.

You may ask, wasn’t Catwoman already a female romantic interest for Batman? Well, under the new rules of the Code, Batman could not be attracted to her in any way, not unless Catwoman first gave up a life of crime, did time in jail, and then became a model citizen. What’s more, there was concern that Catwoman’s sex appeal glamorized being a criminal. So she vanished from comics from 1954 until 1966. Two years before she returned Batman was given a more serious tone again, and both Kathy and Betty were dropped from the stories. They found their way back into the comics many years later.

FAN THEORIES AND READER CONCERNS

Although the Code prevented LGBT ideas from appearing in mainstream comics, it didn’t stop fans from speculating on the sexuality of certain characters. In 1958 the Legion of Super-Heroes was introduced in a Superboy story. The group was a club of teenage heroes native to the 30th century, its members hailing from different planets and wielding lots of strange abilities. The LSH became popular pretty quickly, eventually getting its own series. In 1963 readers met an LSH member named Jan Arrah aka Element Lad, who could transmute substances. The following year, in Adventure Comics #326, Element Lad remarked that he felt out of his element when it came to girls and dating. In a few stories depicting the future of the LSH Element Lad seemed to be the only team member not seen as married or in a romantic relationship. Several readers concluded that Jan was gay, and the LSH fanzine Interlac even published fanfiction that paired the hero off with a male companion.

The Code started to loosen some of it restrictions in the late 1960s. In 1971 several of its guidelines were revised and a few were dropped, which helped usher in a new era of social and political commentary in superhero stories. Vigilantes could discover their friends had hidden drug habits. Villains could be spree killers again for the first time in years. Superman could ponder if his activities stifled human progress. Supernatural entities such as demons, vampires, and werewolves were once again allowed in mainstream comics. But LGBT content was still off the table.

Back to Element Lad for a moment. In 1978 the female character Shvaughn Eric, officer of the Science Police, was introduced in the Legion of Super-Heroes stories. She soon became very close to Element Lad, who was then leader of the LSH. Some saw this as a platonic, spiritual connection. Others took it as a straightforward heterosexual romance, either consistent with Jan having never been identified as gay or as a direct move by DC Comics to quell fan discussion on his sexuality. In the early 1980s, the comics clarified that Shvaughn and Jan were dating and had fallen in love.

But this wasn’t the end of the sexuality discussion for Element Lad. More on that later.

In 1979 the Canadian team of superheroes known as Alpha Flight appeared in the pages of Uncanny X-Men. The team was supposed serve as opponents to the X-Men rather than act as characters in their own stories, so the members weren’t given personal information. Because of this, Alpha Flight co-creator John Byrne was initially reluctant when asked to spin the team off into its own series. Once he decided to do so, he came up with backstories for each character. Team member Northstar aka Jean-Paul Beaubier was now said to be a mutant—a human who had powers due to being born with the X-gene—as well as a former Olympic athlete. Byrne also decided that Northstar was gay. However, he did not directly reveal this in the stories. Instead he only dropped hints, such as having a teammate innocently remark that Jean-Paul didn’t seem very interested in the young female admirers he gained as a celebrated athlete. Byrne also had no problem telling others verbally that Northstar was gay.

Byrne initially declined to say if anything beyond the Code prevented Northstar from coming out, he admitted in recent years that he was also hampered by Jim Shooter, Editor-in-Chief at Marvel from 1978 to 1987. In 2013, Byrne said, “Shooter forbade any overt mention of Northstar’s homosexuality” (thank you to JohnByrneSays for pointing this out). Even before Byrne made this admission, it had been reported for years from different sources that during his time as EIC, Shooter decreed there were “no gays in the Marvel Universe.”

In 1980, Shooter wrote a comic that became a subject of debate. “A Very Personal Hell” was featured in Rampaging Hulk #23 (1980) and intended to place protagonist Bruce Banner into a “realistic” setting of danger and fear. Rampaging Hulk was a magazine targeted at “mature readers” and sold to comic shops rather than public newsstands, so it could sidestep some of the code guidelines.

One scene involves Banner hiding from the police and taking respite at a YMCA. Two men at the YMCA notice Banner and decide he’s quite attractive. They follow him into the shower and make it clear they intend to rape him. Banner’s fear is so great that he can’t even turn into the Hulk (which is not consistent with the many times fear caused his transformation before and since). After escaping his attackers he literally shakes with horror and revulsion at the thought of what could have happened, which triggers the Hulk to emerge and go on a rampage.

Shooter said that this story was meant to give a realistic look at the horror of a violent assault, not to provide a homophobic viewpoint. Critics have argued that, as the would-be rapists were the first characters in Marvel Comics directly identified as non-heteronormative the story comes off as homophobic regardless of intention.

Come back tomorrow for part 2, delving into the comics that defied the Code’s ban on LGBT content and what happened when that ban went away.

Alan Sizzler Kistler (@SizzlerKistler) is an actor and author who identifies as a feminist and just loves comics. He sometimes work as a comic book historian and a geek consultant, and is the author of Doctor Who: A History.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?